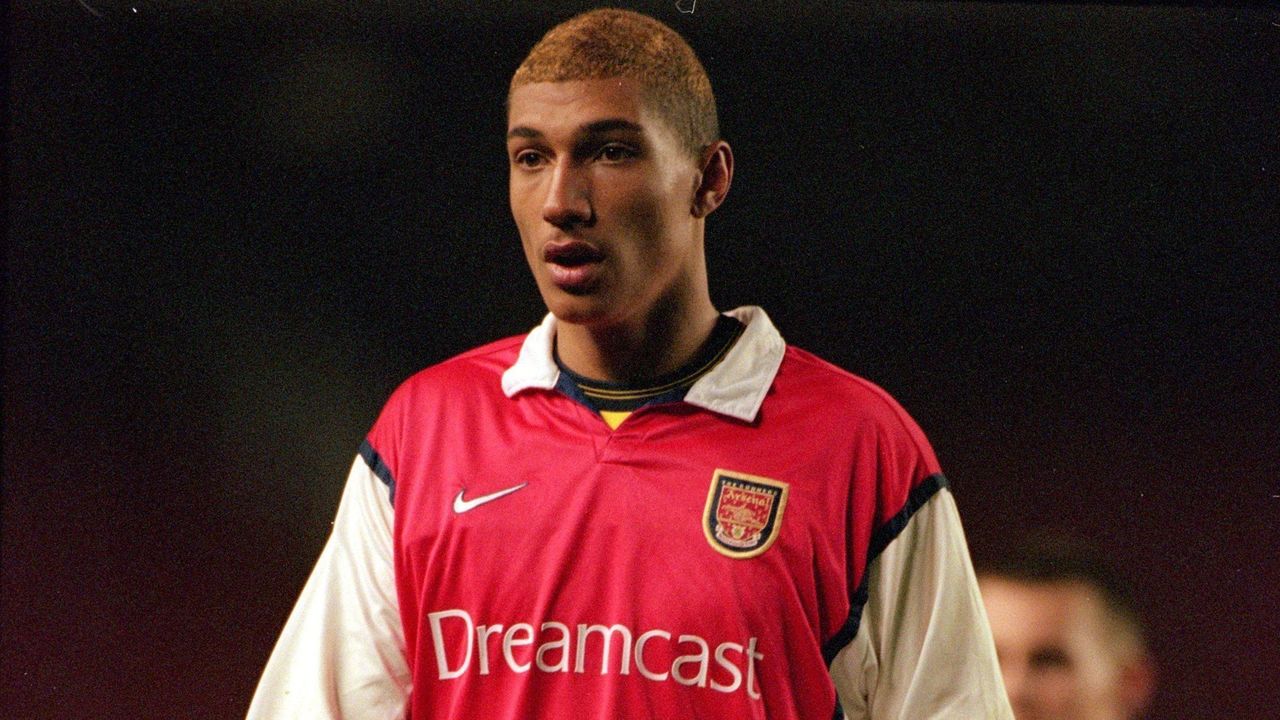

Just days after his 18th birthday, Jay Bothroyd threw his shirt at the Arsenal bench when he was substituted during youth-team duty. It was an error that would dramatically change the course of his career. He was sold less than a month later, abruptly ending an association between one of England’s most promising talents and his hometown club.

“I was around troublemakers. I was around people that broke the law, robbed people, stole. I had people in prison doing 15 years for crimes and these were people I went to school with,” Bothroyd, now 37 and plying his trade in Japan, told theScore about his younger years.

“I stayed away from that because of football. I was always at the park with my dad practicing but, obviously, I did have these kinds of friends. There was a certain way about me. I had anger problems.”

Despite those obstacles, Bothroyd progressed at Arsenal from being an “Alan Smith-like” target man to a forward who, with Arsene Wenger’s influence, sharpened the technical elements of his game and confidently dribbled at defenders. He joined Coventry City for around £1 million in 2000 as a teenager despite having yet to play a senior minute and facing concerns over his discipline.

Many correctly predicted an eventual England call-up for Bothroyd, but his messy exit from Arsenal indicated what was to follow. His story either side of that single international cap has been a tumultuous and highly unconventional journey.

Madcap spell in Italy

Bothroyd speaks highly of Gordon Strachan’s management at Coventry, but he would experience the first truly transformative step in his career with Perugia. He surprisingly left the Sky Blues for Italy in 2003.

Future World Cup winner Fabio Grosso, buccaneering Brazilian full-back Ze Maria, and the wisened Fabrizio Ravanelli offered Bothroyd an extended look at footballers who prioritized the sport over extra-curricular activities. The Englishman took note, and started to take greater care of his conditioning. He previously believed weight-lifting was just for injured players, not those who were already fit.

Bothroyd also immersed himself in Umbrian culture and met his wife in Perugia, but he didn’t bond much with his Italian colleagues. He instead struck up a friendship with Al-Saadi Gaddafi, son of the now-deceased Libyan dictator Muammar, who was combining his playboy reputation with a few eyebrow-raising years as a professional footballer. Although Bothroyd no longer has contact with Saadi – the Colonel’s third son has since faced torture and murder charges – he defends their old bond.

“He was never that kind of tyrant person. He was always friendly, he was always kind. He came to my wedding, he paid for my honeymoon. I had a lot of nice experiences with him,” Bothroyd explained.

“As much as people might say ‘Jay’s crazy, whatever,’ I can only go by what I see … I’d never seen no attitude of violence from him at all.”

Bothroyd counting the offspring of an oppressive ruler as a teammate and friend was a wacky subplot that, at the time, was typical of Perugia.

The club was run by Luciano Gaucci, an eccentric businessman who acquired his wealth through a cleaning company and racehorses. Bothroyd described Gaucci as “a bit crazy,” and remembers the day the owner lost interest and left with little regard for continuing to cover the players’ wages. Over 14 years since he left Italy to return to the United Kingdom, Bothroyd says Perugia still owe him around €70,000.

“I got some money, like €40,000 or something like that, a few years ago but I’m still waiting for this bit now,” he said. “Apparently, they’re trying to sell this big castle they’ve got in Rome and no one’s buying it, but once they sell that I’ll get the rest of my money.”

‘He tried to headbutt him’

Name an old-school British gaffer, and Bothroyd has probably played for him. Graeme Souness, Mark Hughes, Alan Curbishley, Mick McCarthy, Tony Pulis, Dave Jones, Neil Warnock, and Harry Redknapp all oversaw Bothroyd in the period between Perugia and his Asian adventure.

Most of those managers are regularly accused of being tactically limited and belonging to a bygone era, but Bothroyd won’t criticize them; except for Ireland’s current head coach, that is.

“He didn’t let me train when the first-team squad was there. I had to go in the afternoon and do running sessions, just run around the pitch with (fitness and conditioning coach) Tony Daley,” Bothroyd shared of his difficult relationship with McCarthy at Wolverhampton Wanderers.

? Throwing back to 2006…

Mick McCarthy’s first win as Wolves boss came at Molineux via this fine Jay Bothroyd strike!

?? pic.twitter.com/ETJgZTpYs8

— Wolves (@Wolves) August 9, 2019

Bothroyd acknowledges he was troublesome at Arsenal and was still striving to reform his reputation when he was made an early signing of McCarthy’s Wolves reign in 2006. But, after finishing his debut season as the club’s top league scorer, he was strangely out of favor by the second campaign. Bothroyd recalled being stripped of his squad number while McCarthy signed a raft of players in the same position and actively excluded him.

A keen cyclist, McCarthy would sometimes mount his top-of-the-line bike and deliberately torment Bothroyd by making him journey through the forest with him. His player would often trail behind on the beaten-up bike he was saddled with.

“He was doing anything to try and annoy me, try and get me out the door. I knew that,” Bothroyd recalled. “So, obviously, I was doing things to show he couldn’t break me mentally. So, I’d go in the morning with a big smile on my face – ‘Morning gaffer, how’s it going?'”

McCarthy didn’t see the funny side of Bothroyd’s antics. In fact, the attacker found the real McCarthy clashed with his sharp-witted and jovial portrayal in the media. He could unexpectedly turn aggressive.

“Garry Breen was Ireland’s captain for certain games and Mick McCarthy signed him. He was almost like his son,” Bothroyd said. “Then one day, Breen made a mistake in a game and McCarthy came in and tried to headbutt him.

“Then he tried to make Breen apologize to him in front of all the players.”

“Everyone thinks McCarthy’s a laugh and he’s funny and he’s got this way about him, but to me, he’s just two-faced,” he continued. “He’s just not a good coach really in my opinion.

“His idea of a good training session was kicking balls into the channels and saying, ‘Run after that.’ I wasn’t groomed like that. I was groomed in passing football, not just running like a headless chicken. In my mind, I find it very strange that he said I had a bad attitude, but three years later Jones had no issues with me and I was playing for my country.”

The proud Londoner thrived under Jones at Cardiff City and believes he benefited from his boss repeatedly talking him up as an international-quality striker in the media. Fabio Capello’s right-hand man and the Three Lions’ general manager, Franco Baldini, soon watched Bothroyd six or seven times as he notched 15 goals in the opening months of the 2010-11 Championship campaign. Bothroyd was called into the senior squad in November 2010.

England’s training sessions were held at Arsenal’s Colney training base and Bothroyd felt smug as he encountered his former coaches at the club. As far as he was concerned, his call-up proved the Gunners’ mistake in letting him go. He emerged from the bench in a 2-1 defeat to France and shared a debut with Jordan Henderson and Andy Carroll.

A new start

Capello wanted to involve Bothroyd in more squads so sent Stuart Pearce to watch him in Cardiff. Unfortunately, injuries inhibited his ability to participate in training and fixtures for the rest of the season. By the time fellow frontmen Danny Welbeck, Daniel Sturridge, Fraizer Campbell, and Raheem Sterling had all made their England debuts, Bothroyd was a Queens Park Rangers player on loan at Championship side Sheffield Wednesday.

His reunion with ex-Cardiff handler Jones in South Yorkshire wasn’t as fruitful as he continued to be unlucky with injuries. Bothroyd needed to revive his career with a move and, typically, his solution came straight from left field.

“The money was good. That helped me make my decision,” Bothroyd admitted about joining Thailand’s Muangthong United in January 2014. “But, obviously, after preseason when I got to play against the actual teams I realized that the standard was poor.

“It was hard to be motivated when the standard was so poor and the league was so disorganized at that time.”

But Bothroyd’s Thai stint boosted his reputation in Asia and soon opened the door to Japan, a country he admired from afar due to his appreciation for footballers who had played there – from Samurai Blue icon Hidetoshi Nakata to English legend Gary Lineker – and the vastness of its modern stadia.

He was first snapped up by Jubilo Iwata, whom he helped to promotion into the J1 League, before swiftly installing himself as a fan favorite at Hokkaido Consadole Sapporo after his 2017 switch.

Bothroyd is reluctant to move into management and subject his family to more upheaval after his nomadic playing career, so he envisions a London homecoming after he hangs up his boots. Just don’t count on that happening soon. Bothroyd netted a hat-trick and a crucial equalizer over the past two J1 League matchdays and isn’t off the pace alongside players half his age. The fans love him.

“As much as my career could’ve gone better if I had a better attitude when I was younger, I still achieved everything that I wanted to,” he said.