In Villa Fiorito, the shantytown where Diego Armando Maradona was born, it was necessary not only to hustle but also to find joy in the simplest of things. Anything loosely resembling a soccer ball was enough to put a smile on Maradona’s face. Whether it was rolled-up newspaper or a piece of tin foil, he’d kick it on his way to school. When he got a real ball as a 3-year-old, he went to sleep with it. Soccer was his salvation.

One of the poorest areas in all of Argentina, Villa Fiorito could’ve crushed his dreams. Instead, it gave him his soul, his street smarts, and the skills he’d become known for around the world.

“There are many people who are scared to admit that they come from a villa,” Maradona once said, “but not me because if I hadn’t been born in a villa, I wouldn’t have been Maradona.”

It’s where he learned how to dribble in tight spaces and where he cultivated his left-footed genius. The muddy surfaces were his canvas. If he hadn’t been born in a villa, Maradona would’ve lost the very fighting spirit that helped him turn average teams into title contenders.

And if he hadn’t been born in a villa, he wouldn’t have become the people’s champion. Despite his vices – and there were many – Maradona was so beloved precisely because of his humble beginnings. Other sportsmen can seem aloof in their greatness, so far removed from the audience, but Maradona was the people’s elected representative.

Largely inhabited by scores of working-class immigrants who sought new opportunities, Argentina founded its identity through soccer, and Maradona exemplified it. The general struggles of poverty were as much a part of his story as his country’s, and the streetwise entrepreneurship that inspired his game was a shared trait. The drug use and addictions that followed, the many wars with the media, and his struggles with both expectation and the cynical business of soccer were all tragic consequences of his early fame. But those flaws humanized someone who’d otherwise seem so completely out of this world.

As success increased exponentially, Maradona split into two. His ex-wife, Claudia Villafane, believed he had led a double life to cope with the stress of being a savior to so many people, particularly to the citizens of Naples. It was there where he achieved what he described as the biggest accomplishment of his career: winning the Italian title in 1987 with a team that had been battling to avoid relegation three years prior.

At times, Maradona’s two worlds collided. High on drugs, he’d return home to his villa on the outskirts of Naples early in the morning and hide in the bathroom, afraid his two young daughters would see him in such a state.

“With Diego, I would go to the end of the world,” Fernando Signorini, Maradona’s physical trainer, said in the player’s self-titled 2019 documentary. “But with Maradona, I wouldn’t take a step.”

To make sense of his legacy after his death at the age of 60 requires a full portrait of the man. It’s complicated and messy but also beautiful and unique. It’s not just a story about one of the greatest players of all time; it’s about a boy who was forced to grow up and then exploited by those around him and victimized by the often-brutal and violent tactics of 1970s and ’80s soccer.

In 1983, a vicious tackle by Andoni Goikoetxea shattered Maradona’s ankle. During the 1986 World Cup, he was punched in the face, and later in his career, his lower back throbbed with pain, requiring several injections every week. The rules of the sport were mere suggestions. Maradona, as he’d always done, did what he had to in order to brave the conditions, even if it meant skirting the rules himself.

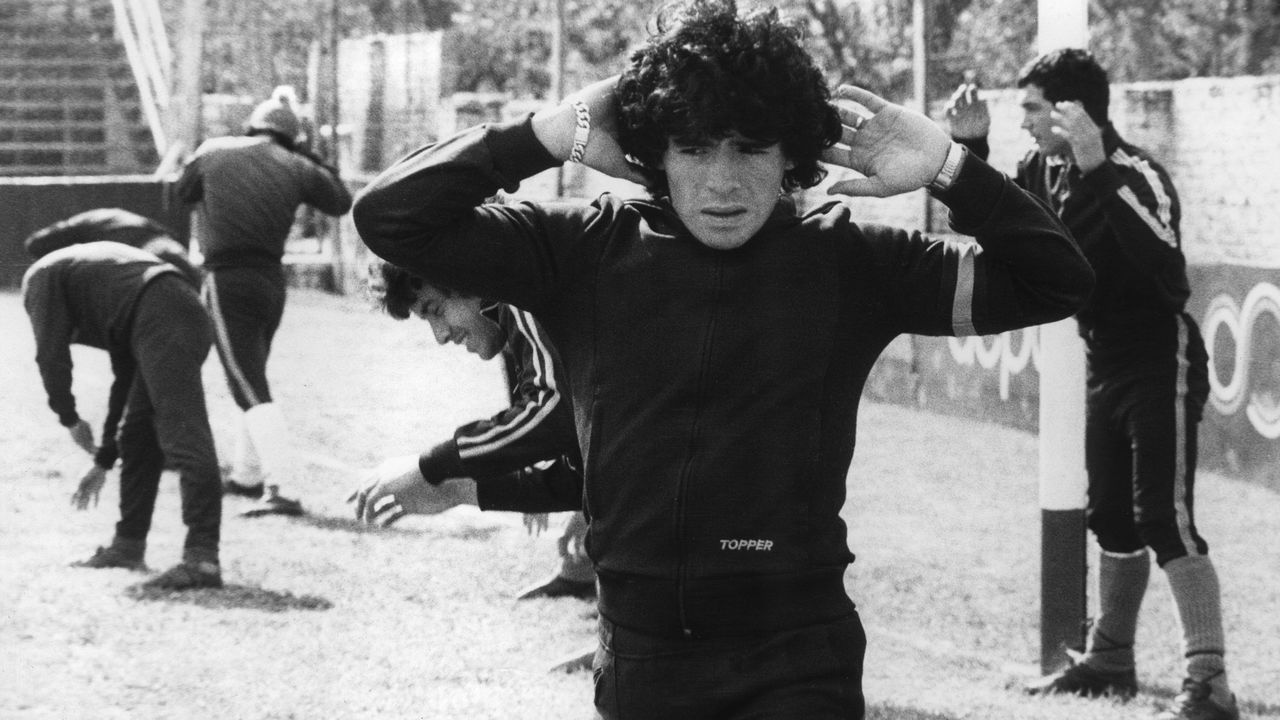

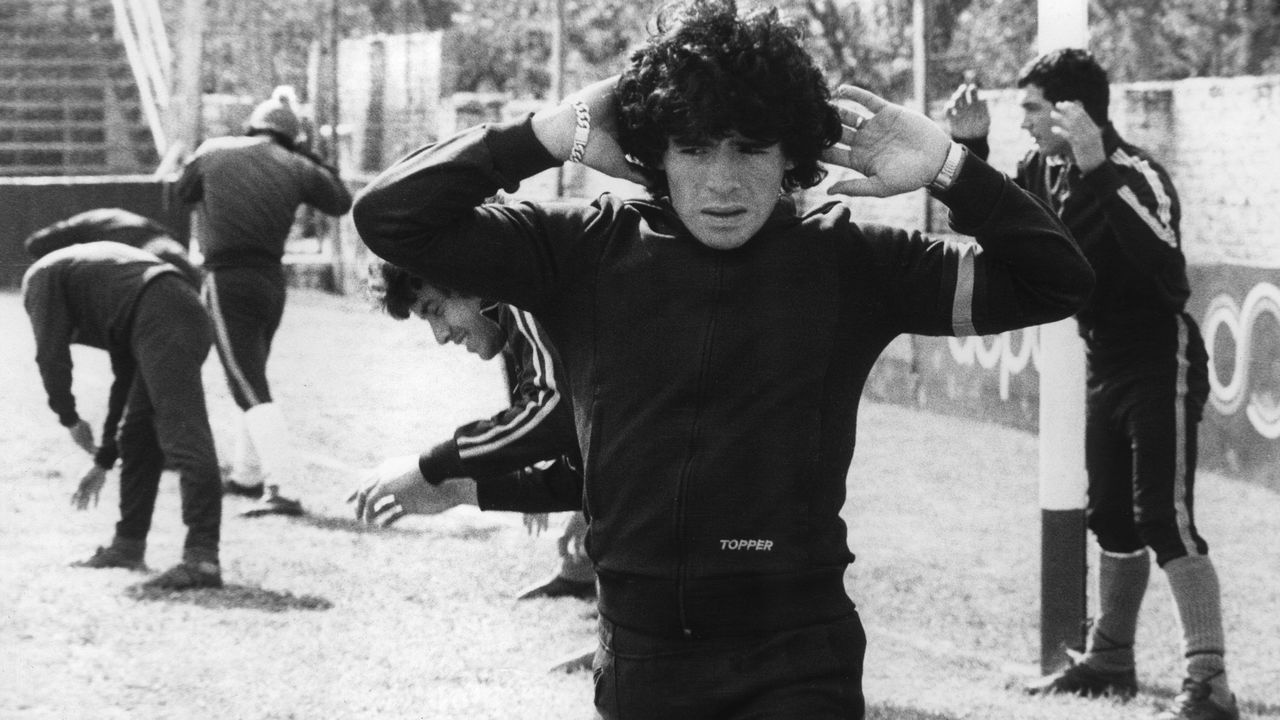

The freedom that defined his early childhood didn’t completely vanish, but it slipped away over time. The need to provide for his family as a 15-year-old took an obvious toll. By the time he joined Argentinos Juniors in 1976, his father had quit his job and Diego and his family had moved into an apartment that the club bought for him.

The need to be “Maradona” every week became a chore. Sometimes, he’d play four times a week to accommodate the people who were paying his growing salary. Shortly after he joined Boca Juniors in 1981, Maradona became a traveling act, playing in friendlies to bring in cash and keep the club’s debt at bay.

Later, at Napoli, club president Corrado Ferlaino forced Maradona to stay against his will. Ferlaino eventually called himself the player’s “jailor.” Then 29, the playmaker had grown weary of Naples and its feverish supporters and sought to wind down in a calmer league. The fanaticism was relentless. Fans would mill around his house and mobs of reporters and photographers chased after him.

He was uncomfortable with the fame. Neapolitans often had pictures of Maradona above their beds, watching over them like Jesus Christ. One nurse administering a blood test stole one of his samples and placed it in the Church of San Gennaro, the city’s patron saint.

The Partenopei went on to win a second title in 1990, with Maradona finishing third in scoring, but his personal crises intensified.

Naples is “where his life derailed,” Jorge Valdano, who won the 1986 World Cup with Maradona, wrote in El Pais. “The joy and the pain, the light and the darkness, the highest peak and the deepest pit. Health, which was soccer; and the disease that spread through his life. No one that I know made such a long and winding journey.”

Maradona got everything he wanted. And that was part of the problem. Everyone was happy to indulge his wants and desires, but it was dangerous. He became a political pawn, propped up to show the strength of southern Italy, and he became close with the Camorra, a branch of the Italian mafia. Camorra boss Carmine Giuliano would give Maradona the protection he so desperately wanted and throw parties after games. Cocaine, which comforted Maradona during two injury-ravaged seasons at Barcelona, was all too available.

Maradona entered a vicious cycle. He’d party for several consecutive days and spend the latter half of the week detoxing and getting back into shape. Maradona may have been a god to the people, but the mafia had control over him.

The Camorra discarded him when his cocaine use became public knowledge. All the protection he had was gone. When Maradona failed a drug test in 1991, he was banned from soccer for 15 months.

“It was brutally damaging,” Signorini, his former trainer, said, “but the people that ran the business only cared about getting the most out of him. And if he ended up in pieces, then f— him.”

It was different on the pitch. No matter what was happening around him – rumors of infidelity, talk of an illegitimate son, hearsay about his drug use – Maradona kept winning and pleasing the masses. He slalomed through the pitch like a skier downslope and had a ridiculous, unrivaled command of the ball. He could arc a free-kick into the top corner, fashion the perfect pass into the area, and take on several defenders at a time. The people of Naples didn’t have what Italy’s other cities had – clean water, education, gainful employment – but they had Maradona.

And the city was cut in his image. Maradona shared the same underdog background and the same rebelliousness as Naples, which never fit into the beautified image of Italy. He enjoyed playing for the working class, just as he did in Argentina, because that’s the world he knew. He thrived on teams that lacked the fanfare and funds of their rivals. They followed a similar plot to his own personal story, rising from the doldrums to achieve things beyond their wildest expectations. Napoli were like this, and Argentina’s national team too. He didn’t win anything with Argentina’s talented 1982 World Cup squad – getting sent off against Brazil – but inspired a lesser team in 1986 when he was named captain.

“The unique achievement of Maradona, when he is compared to the contenders to be considered the greatest player of all time, is to have led, almost single-handedly, a moderately sized club to a major championship in an era in which money had started to be not merely an advantage but a decisive factor,” Jonathan Wilson wrote in his book, “Angels with Dirty Faces.”

“It wasn’t just about his technical ability, about his gambetas (dribbling), his free-kicks, and his goals, but about him as an inspiration and an organizer. Of the other greats, perhaps only Cruyff – although in a different way – could match his on-field tactical brain.”

That leadership goes a little underreported. When Napoli won the UEFA Cup in 1989, Maradona embraced Ciro Ferrara, a native of the city, as reporters encircled them and explained how much this victory meant to his teammate. Though he’s known for deception – owing to the infamous “Hand of God” at the 1986 World Cup – he could show humility at the heights of his glory.

Maradona was never the same after his experience in Italy. The media mocked his addictions and labeled him a crook and a cheat. He acted differently, too, raging against FIFA and accusing it of conspiring to end his career. He refused to accept responsibility for his failed drug test and argued the Italian authorities were out to get him ever since he and his Argentina eliminated Italy from the 1990 World Cup. In Italy, he was accused of tax evasion, and in Argentina, he was arrested for cocaine possession. In 1992, he joined Sevilla. He quit 12 months later, overweight and critical of the coaching staff.

Yet the majority of Argentina still loved him. The people were inclined to believe Maradona’s conspiracy theories and were happy to see him back with the national team at the 1994 World Cup. He scored an outrageous goal against Greece in the group stage – a powerful shot from the edge of the penalty area that found the top left corner.

But what began as a sort of redemption tour ended with the sobering reality that the great Maradona was a broken man. He was kicked out of the World Cup after testing positive for a cocktail of substances, prompting a day of mourning back in Argentina.

That last goal against Greece wasn’t a sign of a comeback. It was a farewell.

“Having beaten the keeper, Maradona wheeled away to celebrate, suddenly spotted a camera, ran over to it, and roared into the lens – like some wounded beast,” author Juan Villoro wrote in his book, “God is Round.” “The untouchable, the lion, in the eyes of FIFA, was back in his kingdom. The victim of so much admiration was out for revenge.

“He never got it.”